|

| CC0 Public domain by Kaboompics on Pexels |

The evolution of MOOCs is largely an experiment in scaling online education; how massive can a course be? The answer would seem to be that a course can be very massive under the assumption that the learners are highly motivated, confident, independent and digitally skilled. Everyone else needs support, encouragement and a feeling of belonging to a caring community and that is hard to achieve in a massive environment. Combining scale with a feeling of community and personal support would seem to be an impossible equation.

Lisa Nielsen takes up the issue of class size in a post called It’s Class Load, Not Just Size, That Matters. She describes how teachers often have to deal with many large classes and an unrealistically high number of students making personal contact and support for all simply impossible. Students who lack confidence need lots of encouragement and feedback and study skills need to be actively developed. Teaching and counselling generally go hand in hand but the latter is seldom recognised in an age obsessed by results. For Lisa the solution is clear.

If we want students and teachers to succeed, increase the time students spend with their teachers and limit the load. It’s a simple solution where everyone wins.

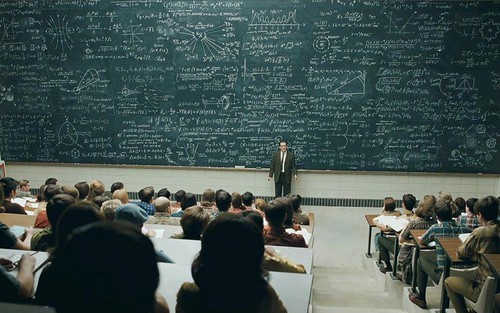

This is an important discussion for all educational institutions. Large classes in lecture halls are certainly impersonal and lack support and recognition. I once heard the remark that if you sit more than five rows from the front you can call it distance learning. But how does this apply to online learning and in particular the massive variety? Once the teacher student ratio goes above 1:150 the load becomes impossible and the course becomes increasingly self-directed study. There are, however, a number of possible solutions:

- Involving more teachers and teaching assistants. This can often become prohibitive in terms of costs but one solution can be a network of teachers and former students. One example of this is a course I work with called Open Networked Learning. This is an open online course run in partnership between a number of universities and which also welcomes open learners. We have a core team of four who manage the course and then a large number of facilitators and co-facilitators (volunteer former participants) who support the learners during the course. This means that the learners can be divided into many small study groups where they support each other and get the support of assigned facilitators and co-facilitators. This model works very well but is not massively scalable and relies very much on the goodwill of the co-facilitators..

- Local support groups. Libraries, adult education colleges or community learning centres can offer a meeting place to help people discover and follow open education courses. By offering a physical (or also online) space as well as support staff the learners can discuss their courses in their own language and get the encouragement and feedback they need to keep going.

- Peer support. Many MOOCs now offer learners the opportunity to form their own study groups where they can discuss (often in another language than the course language) and get the recognition and feedback necessary to maintain their motivation. The problem here is that most people need clear guidelines on how to build an online group and provide effective peer support.

All of these avenues are being explored today and the answer for massive courses may be a combination of all of them. The key element however is that whatever the scale there must be personal connections. Automated self-study can only take us part of the journey.